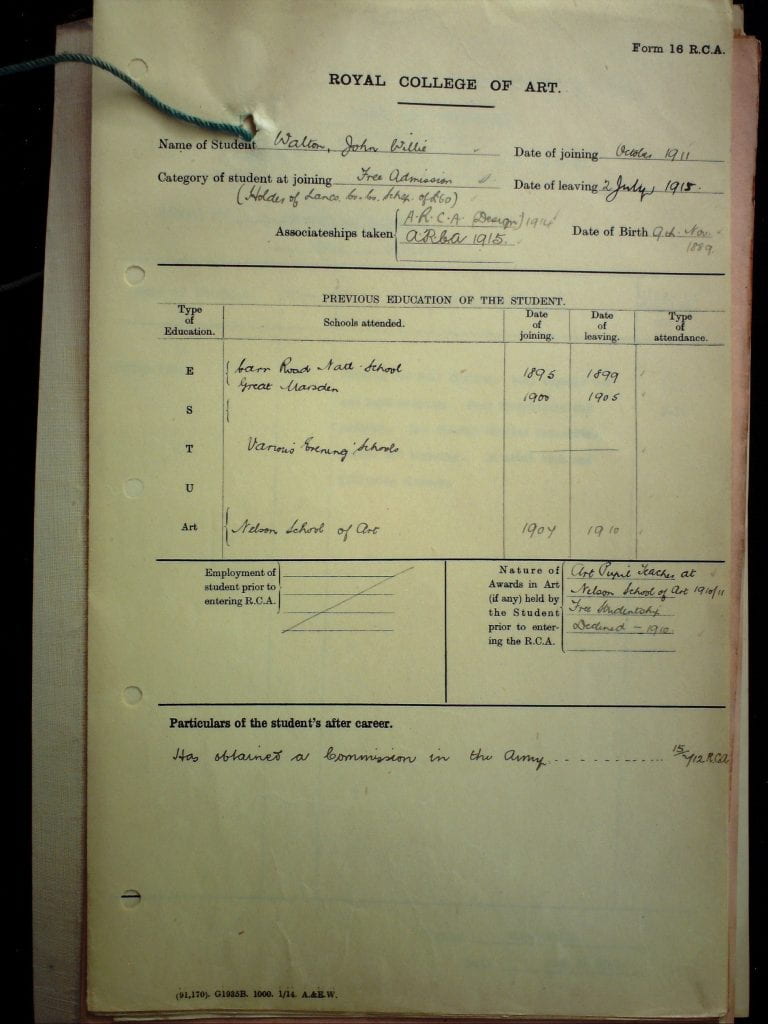

Born: 9 November 1889

Died: 3 December 1918

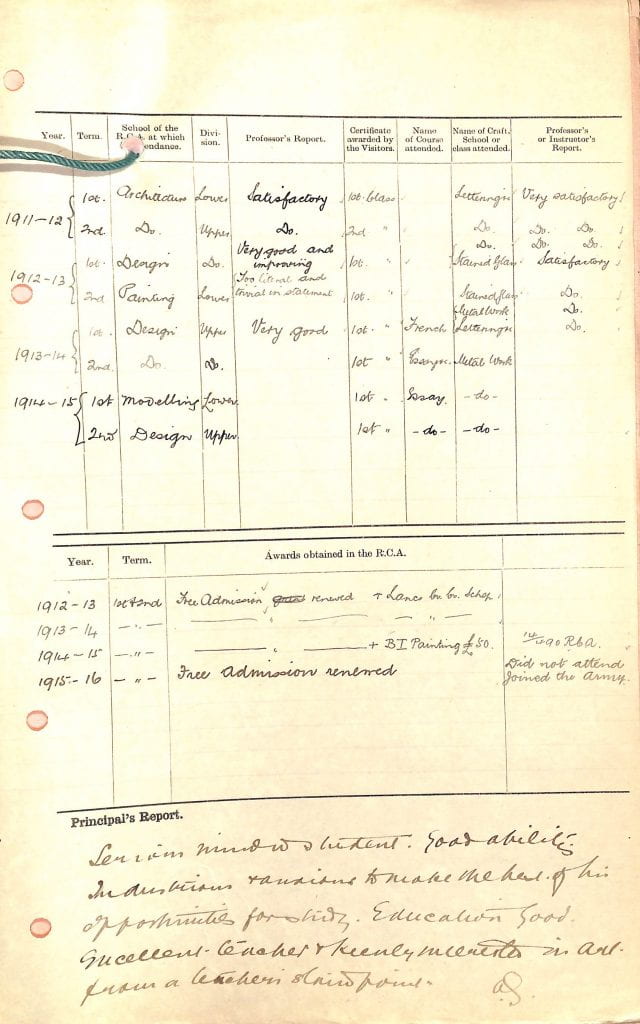

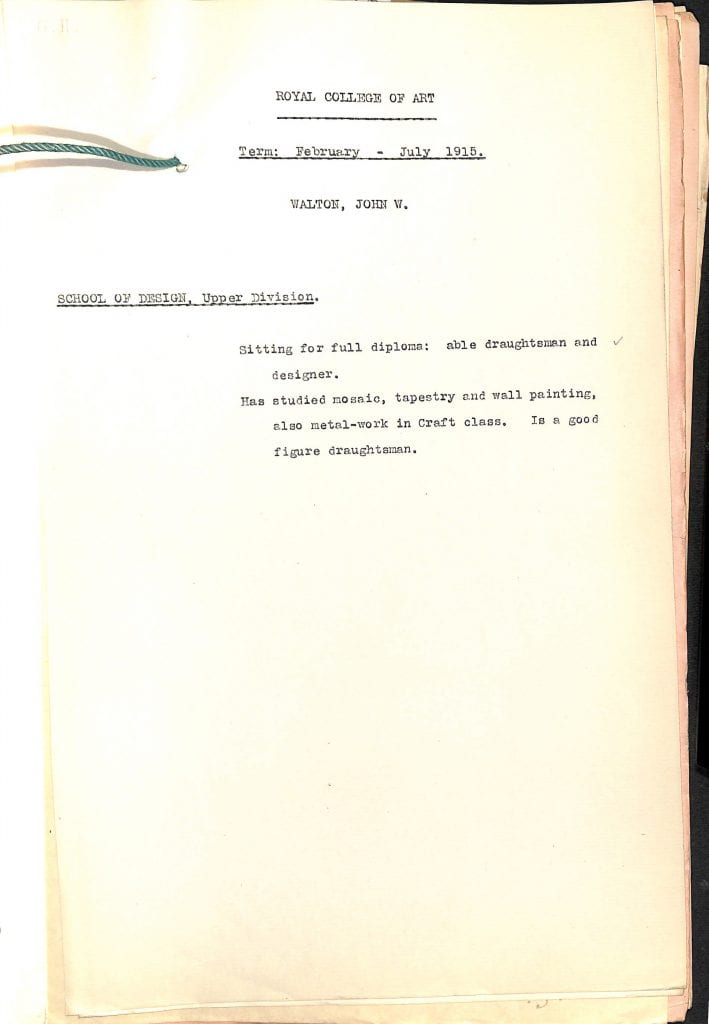

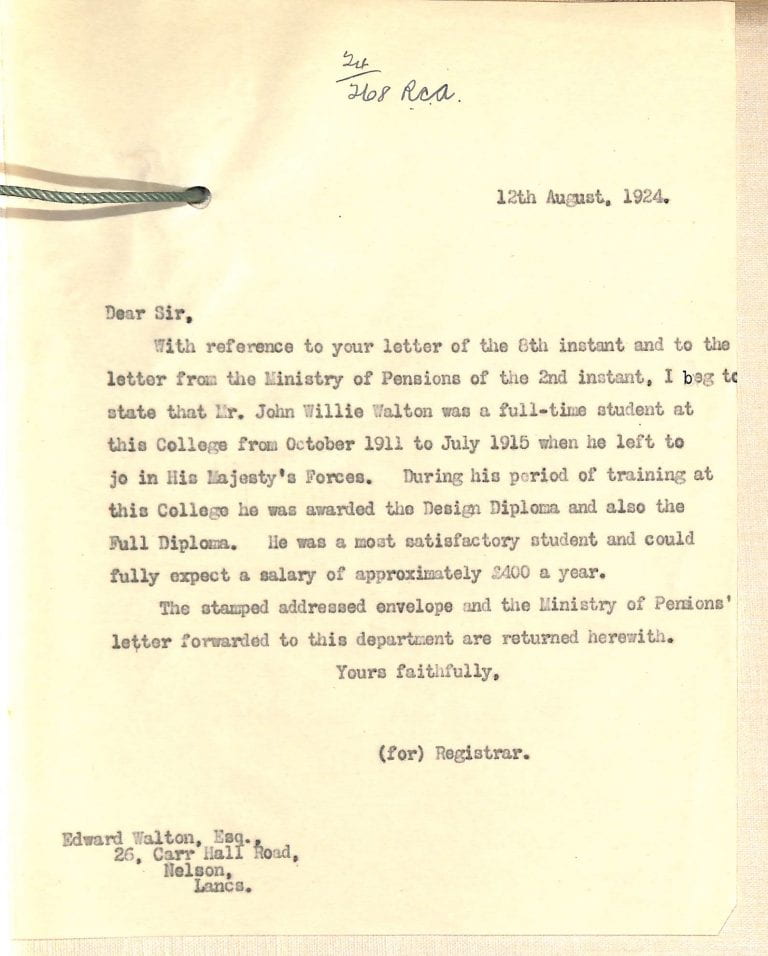

Studied at RCA: October 1911- 2 July 1915, ARCA Diploma (Design) 1914, Full Diploma 1915.

John Willie was born and brought up in Nelson, Lancashire. He was one of four surviving children of John (senior), a well-known cotton goods manufacturer with political ambitions, and his wife, Mehetabel (or Mehitabel). John Willie is noted in the 1911 census as living with his father, by then widowed, and younger sister. His ‘Profession or Occupation’ is described as a ‘Fine Art Student’ while his later RCA student file notes that he was an art pupil teacher at Nelson School of Art (and that a free studentship there had been declined). Within a couple of months of the census being taken John Willie had married Flossie Leach, a cotton winder, with their June marriage certificate describing him as a ‘clerk’ – as do later College forms – perhaps indicating that at least some of the time, or at that particular time, he may have worked for his father. Somewhat surprisingly, the witnesses for the couple, apart from their respective fathers, included their teenage siblings.

In contrast to his situation at home John Willie was able to attend the College with the benefit of a local scholarship and free admission. This must have been useful, as he was not alone in London: a note in his student file dating from March 1912 relates to his taking Flossie back to Nelson due to illness, while later sources suggest she may have returned to London and continued to live with John Willie, at least while he was studying. The College reports on his progress note how capable and hardworking John Willie was, with particular strengths in ‘figure draughtsmanship’ and design.

In the autumn of 1915, despite the granting of yet another year of free admission, John Willie left to join the Royal Navy Air Service (RNAS) rather than the army: perhaps he had noticed and become interested in their ballooning activities at the Hurlingham Club grounds, near to where he and Flossie were living in Fulham. The role of non-rigid, tethered kite balloons has largely been forgotten but their observations during the war were hugely significant for operational planning on land and, by 1915, coastal waters and at sea. They had a key advantage over aeroplanes – direct and immediate communication with those below using a telephone connection. They were, however, vulnerable to the weather and attack so came kitted out with escape parachutes, unlike other aircraft.

Towards the end of October the RNAS acknowledged the receipt of a letter from Augustus Spencer (the College Principal) ‘recommending Mr. J.W.Walton’, presumably as a potential officer, noting that after only ‘a week’s trial Mr Walton has already been promised a commission in the ‘Kite Balloon Sections’. John Willie’s service file shows that he had become a probationary Flight Sub-Lieutenant on 23 October, subsequently completing a course at Wormwood Scrubs during November: the open common had long associations with the military. After this he continued training at the RNAS’s base in Roehampton with his skills in ‘panoramic sketching’ soon recognised, along with his showing of ‘great promise’ amongst the consistently complimentary notes in otherwise sparse service files.

In the published Navy List for 3 January 1916 the new crew for Kite Balloon Section (KBS) No.1 is noted as ‘under formation’, preparing to join HMS Manica, the first ship that had been adapted to carry kite balloons during the Gallipoli campaign the year before. John Willie was one of a core group of four pilot/observers that joined the refitted ship at Birkenhead in February. These four remained together for most of the following year, with one of them, Flight Lieutenant David Gill, serving as their commander: in the circumstances they must have formed a very close-knit unit.

On 8 March the Manica set sail for the East African coast, the objective being to help blockade and/or capture German seaports there. During April, while the ship was near Mombasa and Zanzibar, the kite balloon was tested several times: on at least one occasion, a puncture was spotted and mended. Surviving intelligence reports for July, written and signed by David Gill and John Willie, reveal meticulous observations of conditions recorded when the kite balloon was flown, often ascending to over a thousand feet, several times each day. Apart from recording the weather they were also hoping to spot enemy camps in plantations, or possible activity such as raiding parties in the bush below. Most of the time, however, this work must have been repetitive and dull. The most significant action John Willie took part in during this posting came on 15 August with an attack on Bagamayo (once a major centre for the slave and ivory trade). John Willie’s contribution to the capture of the port was mentioned in despatches, his work being ‘…of the greatest use in pointing out the enemy’s line of retreat’. Careful observations may have helped to spare all those seeking sanctuary from shelling who had gathered in the cathedral there.

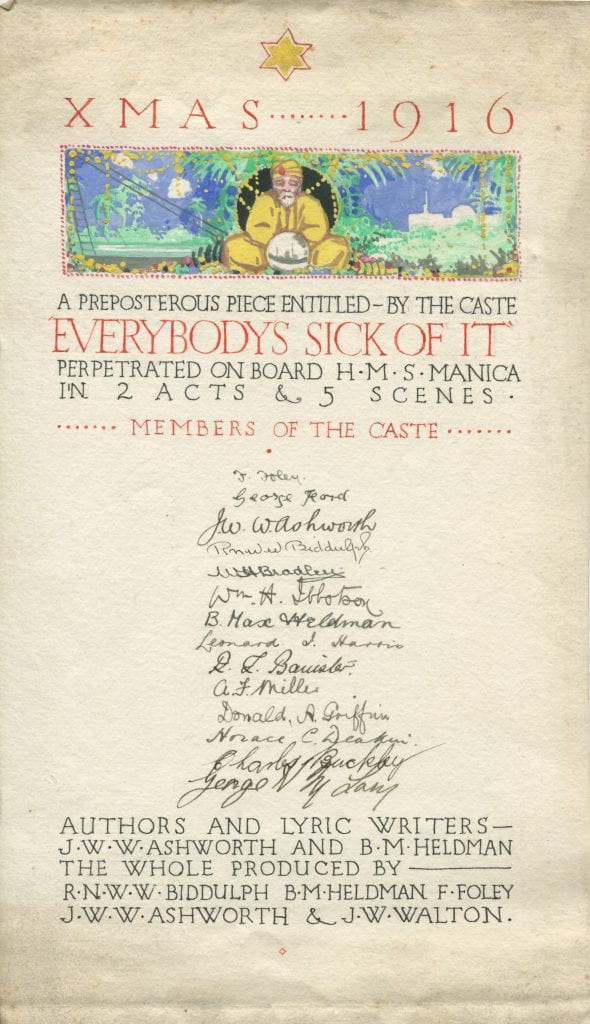

It seems probable that the Manica was still in the area at Christmas 1916, with a playbill for a two-act pantomime naming John Willie as one of the producers (and perhaps the designer of the bill’s artwork). Whether this was ever performed is not known, but concert parties, plays, and self-penned shows were certainly common at this time and were encouraged as a way to keep spirits up. EVERYBODY’S SICK OF IT, the title of this particular effort, suggests a more directly irreverent approach might have been easier for the authorities to tolerate, or ignore, when performances took place far away at sea.

The Manica left the area in the new year, with crew lists changing as several kite balloonists departed for service elsewhere. Records do not show where they left the ship, which does not seem to have returned to British waters, but by July 1917 John Willie, having been promoted to Flight Lieutenant, is listed in KBS No.9 at Milford Haven, Pembrokeshire, presumably looking for submarine activity in the Irish Sea. Just over a month later he moved on to KBS No.15, at Tipnor, near Portsmouth. This base rapidly expanded over the following months, providing patrols and occasional convoy work in the Channel, but it is not clear whether John Willie took part in any of these activities or was helping to train others. His promotion to captain was later recorded as dating from April 1918 with the merger of the RNAS and the Royal Flying Corps to form the Royal Air Force (RAF) the same month – but contemporary records still refer to his being a lieutenant.

By early summer 1918 the RAF had decided that Tipnor staffing (and kite balloon numbers) needed to be reduced. John Willie was relocated, with at least one source suggesting he went first to Balloon Training Base No. 1 at Sheerness in Kent. In August, however, he was back at Roehampton and, at least for a short while, John Willie may have returned to living in the Fulham flat: this is the address he used when joining the freemasons in June. It is not certain whether Flossie lived with him at this time. His will, written in 1917 while he was on board the Manica (witnessed by fellow kite balloonists), mentions that she lived at a different London address, while more curious are some of his service records that include their address in Fulham but crossed through, indicating that Flossie should be written to ‘c/o’ his older brother, Edward, who continued to live in Nelson.

This brief period of perhaps relative domesticity ended when John Willie was posted to HMS Colossus based at Rosyth in Scotland, with the logbook recording that he came on board on 1 October 1918. A kite balloon arrived a week later, but is noted as ‘breaking adrift’ on 10 October. A couple more were supplied by the end of the month as exercises and patrols continued through November, beyond the signing of the armistice: fears remained that the peace would not hold until the surrender of the German Navy on 21 November.

Just over a week later, at noon on Monday 2 December, John Willie is logged as leaving the Colossus. He was taken to the naval hospital close to a kite balloon and airship station at North Queensferry. His RAF casualty card describes his desperate state: ‘Influenza & pneumonia case. Cond. gives rise to anxiety, wife at hosp’l’. Flossie was with him when he died the following day. His card is stamped ‘KILLED’, as if in a battle. He had recently turned 29 years old, his birthday, coincidentally, falling on the same day as another former student, A.W. Peters (see his entry), who had only recently died in the same pandemic.

John Willie was buried at Richmond & East Sheen Cemetery, Greater London.

Edward, John Willie’s older brother, was named executor of his will. John Willie left everything to Flossie. She died of tuberculosis in 1925; her death certificate notes, proudly, that she was Captain J.W. Walton’s widow.