Died: 1 October 1918

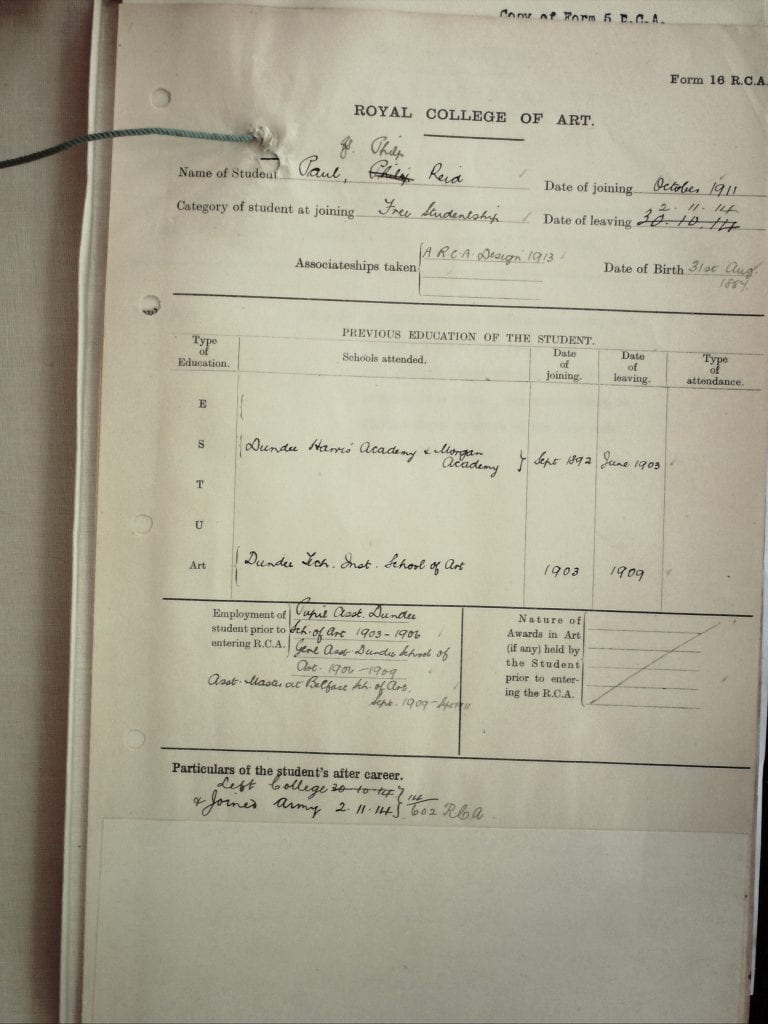

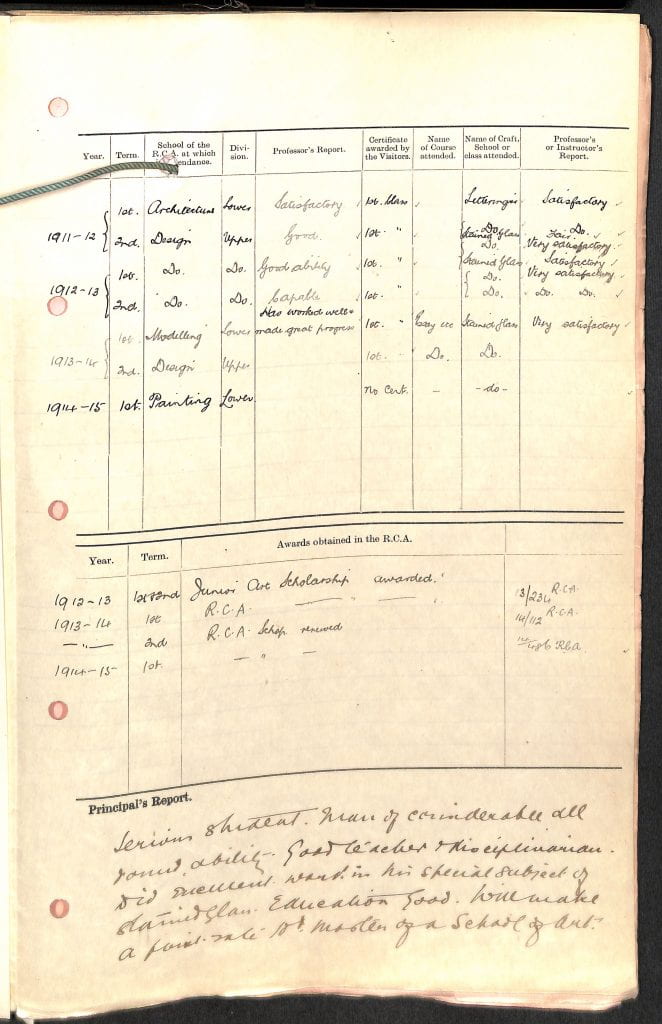

Studied at RCA: October 1911–2 November 1914

Philp – probably pronounced ‘Philip’ if the many misspellings in official documents are anything to go by – was the youngest of three sons of Catherine and Alexander Paul, a Dundee cabinetmaker. He seems to have done very well as a pupil at the Dundee Harris and Morgan academies, and later at the Dundee Technical Institute School of Art, where he was a pupil assistant. Indeed, a later local newspaper report described him as ‘brilliant’. Teaching was the career he was pursuing, and in the three years before he came to the College, he had been an assistant master at Belfast School of Art, covering a broad range of subjects and basic skills.

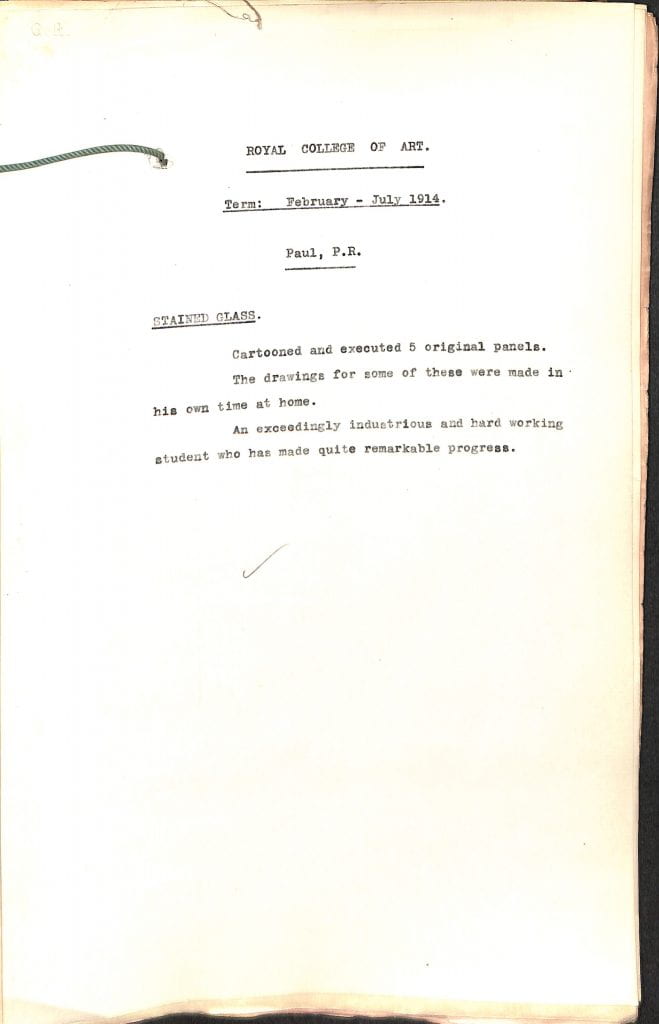

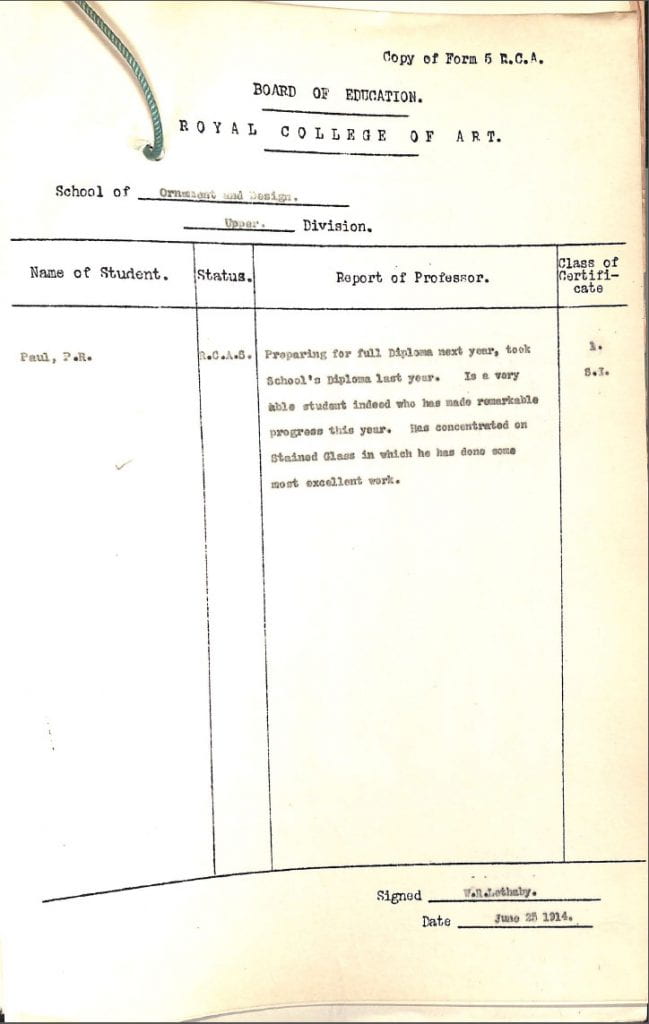

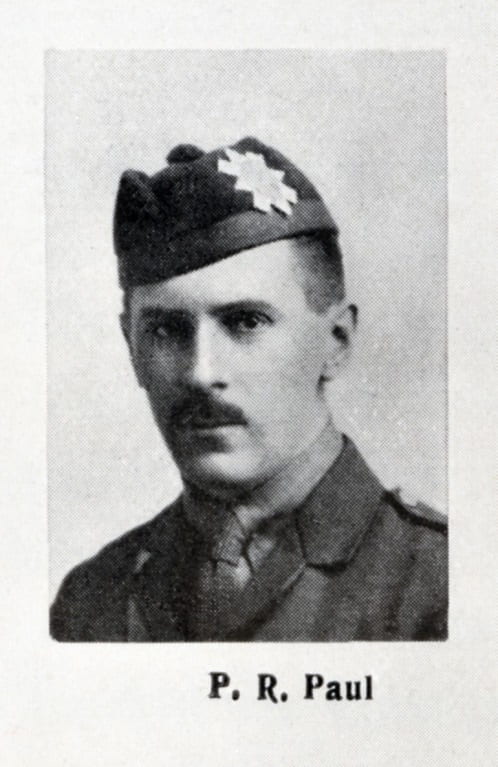

Philp arrived at the College having won a free studentship, but studying there was not an entirely new experience for him: he had regularly attended its summer courses for several years while at the Technical Institute. Apart from his file confirming that he was a ‘good disciplinarian’ and would ‘make a first-rate Art Master’, it also mentions in particular his ‘remarkable progress’ and ‘excellent work’ in stained glass, perhaps indicating a possible alternative career – although his all-round ability is apparent from other reports. He gained his ARCA diploma for Design in 1913, and continued to study for a short time at the beginning of the following academic year, this session concentrating on Painting, before enlisting at Chelsea Town Hall on 30 October 1914. Within just a few days he joined the Royal Horse Guards (the Household Cavalry), based at Regents Park Barracks.

By the end of June 1915 Philp had gained a commission, and in September became a temporary Second Lieutenant with the Royal Highlanders, more familiarly known as the Black Watch. In an informative and good-humoured letter he wrote to the College in December, acknowledging the return of items from his locker, he revealed he was at the time in camp at Aldershot undertaking an instructor’s course in physical training, describing himself as ‘one huge ache’. This is just one indication that he would become, or even at this point already was, an army instructor – continuing to use his teaching skills for other purposes.

At first Philp served with the 11th (Service) Battalion, the Black Watch, but during 1916, and following the introduction of conscription, such were the huge numbers of new soldiers that training provision was reformed into specific battalions and brigades. The 11th Battalion became part of the new 38th Training Reserve Battalion (9th Reserve Brigade), with Philp appearing to have been promoted to temporary Lieutenant, with at least one later newspaper report stating he had been an ‘assistant adjutant’ to his battalion.

His army service continued at home well into 1918 fulfilling this useful role. In March Philp married a Londoner, Ella Caroline May Merret – known as May – the daughter of a former publican. This seems to show that Philp still maintained connections with London, even though his work took him elsewhere: he was based near Cromer, Norfolk at the time of his marriage. But it also could indicate that he was planning ahead, having understood, because of his position in the army, the shock of the ‘Kaiser’s Battle’ and the weaknesses in manpower it had exposed. In June, perhaps anticipating what might happen in the next few months, he sensibly made out his will, naming May as his ‘executrix’.

On 3rd August, Philp’s ‘home service’ came to an end. He embarked for France, now attached to the 8th Battalion, the Black Watch, part of 26th Brigade, one of several in the much-respected 9th (Scottish) Division. By 8 August Philp was assigned to their B company taking part in successful operations west of Bailleul.

It seems apparent that the course of the war was fundamentally changing, with a new Supreme Allied Commander, Marshall Foch, in charge, the presence of US forces and the blockade of Germany taking effect. By the end of September the 26th Brigade were near Passchendaele, west of Ypres in Belgium – an immense achievement considering the disasters of the previous year in this same area – preparing with Belgian forces for the first phase of an attack at Westhoek Ridge. The war diary for the brigade briefly describes the events of the morning of Tuesday 1 October. Operations began at 5.45am, and while initially successful, German forces rallied. Some time between 8.45am and 10.45am Philp is noted as one of several officers killed.

On 7 October, May, his wife of only a few months, received a telegram from the War Office offering sympathy, with a local newspaper, the Dundee Courier, reporting his death the following day. May wrote to the War Office at the end of the month from the home of Philp’s parents, in the hope of beginning to sort out probate: the army were apparently unaware that while her husband did not have a soldier’s will, he had made his own arrangements for his estate.

Philp has no known grave. He is instead commemorated on the Tyne Cot Memorial, Zonnebeke, near Ypres, Belgium.