Studied at the RCA: October 1910–July 1914, ARCA Diploma c.1913

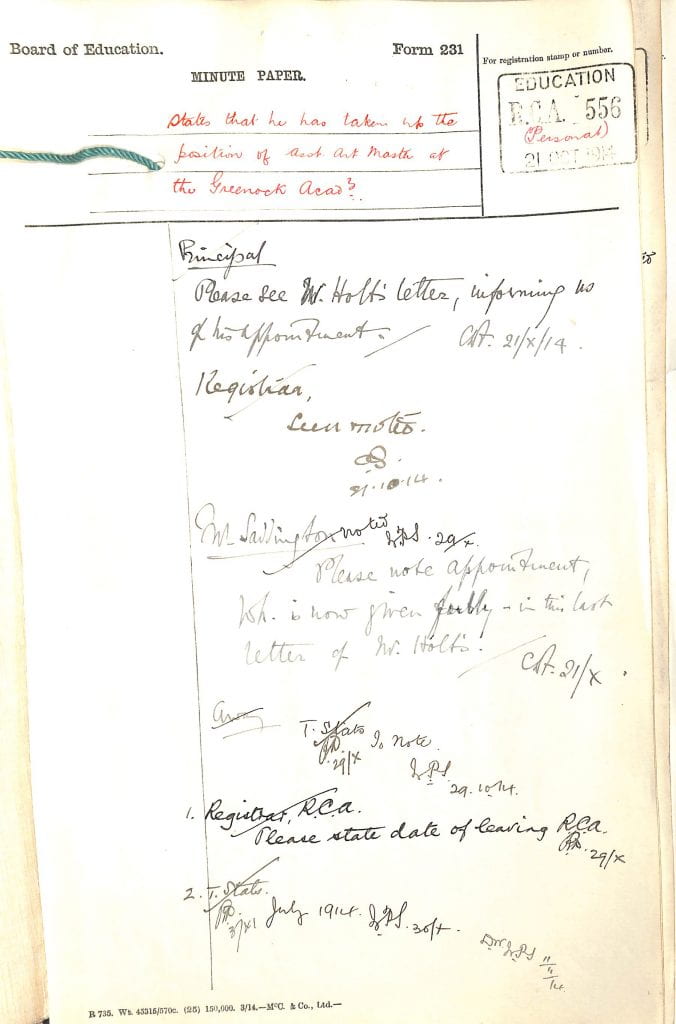

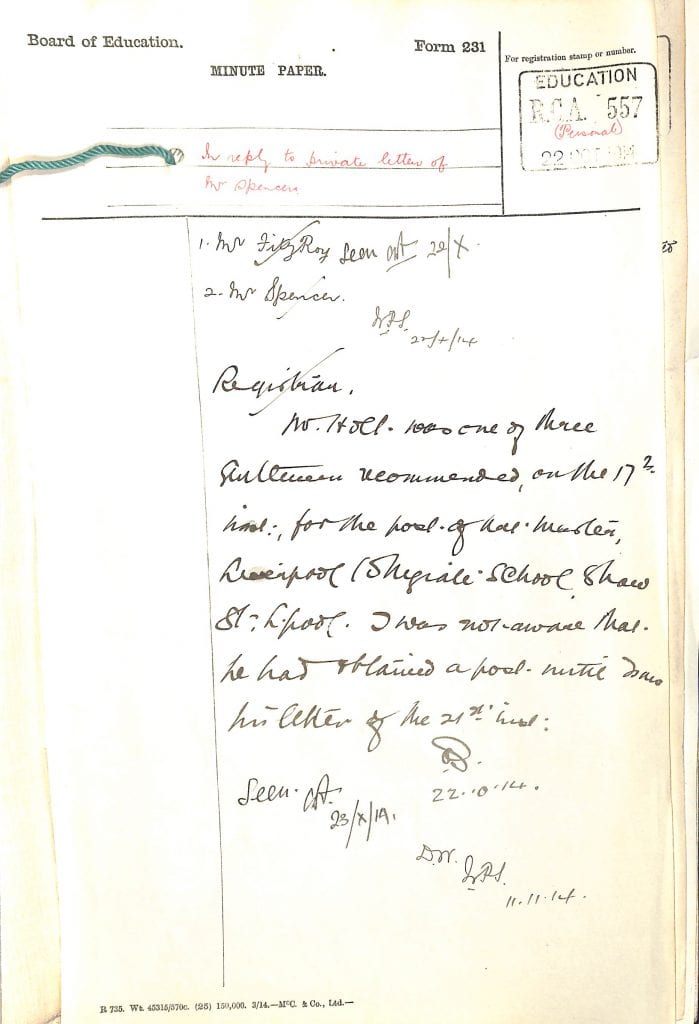

One of four brothers, Wilfred came from a family of Lancashire cotton weavers. At twelve years old he was following the same trade but at some point moved into teaching. Becoming a qualified art teacher was his reason for attending the College, funded at first by a local authority scholarship, and then under free admission. While there he focused on design, and won particular praise for his work with stained glass. He was described in his student file as ‘solemn in manner’ and having ‘a good influence’: these were stock phrases used by the College for anyone considered suited to a teaching career. Wilfred took up a post at Greenock Academy in Scotland in October 1914 without asking for references from the College, apologising in a letter the following year for this and explaining that he had been under pressure to accept when his predecessor had unexpectedly joined up. However, in November 1915 Wilfred also enlisted.

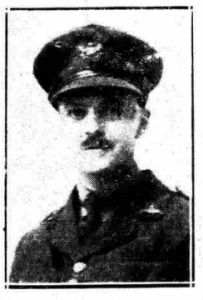

He quickly rose up the ranks, serving at home in the 12th (Reserve) Battalion of the East Lancashire Regiment, and in the summer of 1916 applied for a commission supported by the College’s Professor of Design, W.R. Lethaby. He began his officer training at Prees Heath Camp in Shropshire in the autumn. In February 1917, with the war entering a third year, Wilfred married Alice Shaw. Within weeks, with almost cruel inevitability, he found himself posted abroad as ‘reinforcement in the field’ joining the 12th Battalion of the Manchester Regiment in the build-up to the Battle of Arras.

Like all officers leading men into action, Wilfred was particularly vulnerable and within a month of arriving he was evacuated back to England, having suffered a gunshot wound to his right shoulder. But the need for officers was great, and he returned to Belgium by mid-July, this time attached to the 11th Battalion of the Manchesters, and just in time for the start of the Third Battle of Ypres. His battalion (along with others in its division) did not see action immediately, however, and spent at least a couple of weeks more practising tactics for fighting at Langemarck, north of Ypres.

Things did not start well on the day of the planned attack. Just after midnight on 16 August, Wilfred’s platoon was expecting to be guided to the western bank of the nearby Steenbeek river, leaving plenty of time before zero hour. But they were badly misdirected and had little opportunity to rest or for last-minute preparations before action, crossing the river via duckboards at 4.45 am, when the soldiers were caught in intense artillery fire. Wilfred was one of those killed.

At the time he was buried in a field just north west of Saint-Julien, a village close to the Steenbeek. But for Alice, his wife of six months, now a widow, this was not enough information for her to obtain a death certificate, sort out his will or claim on the life insurance he had taken out. The War Office suggested, in a matter of fact way, that she should write to his commanding officer to find out more.

Two years after the war, Alice was told that Wilfred’s body had been found and would be moved to a war cemetery. Wilfred was re-buried at New Irish Farm Cemetery, Ypres, West Flanders, Belgium.