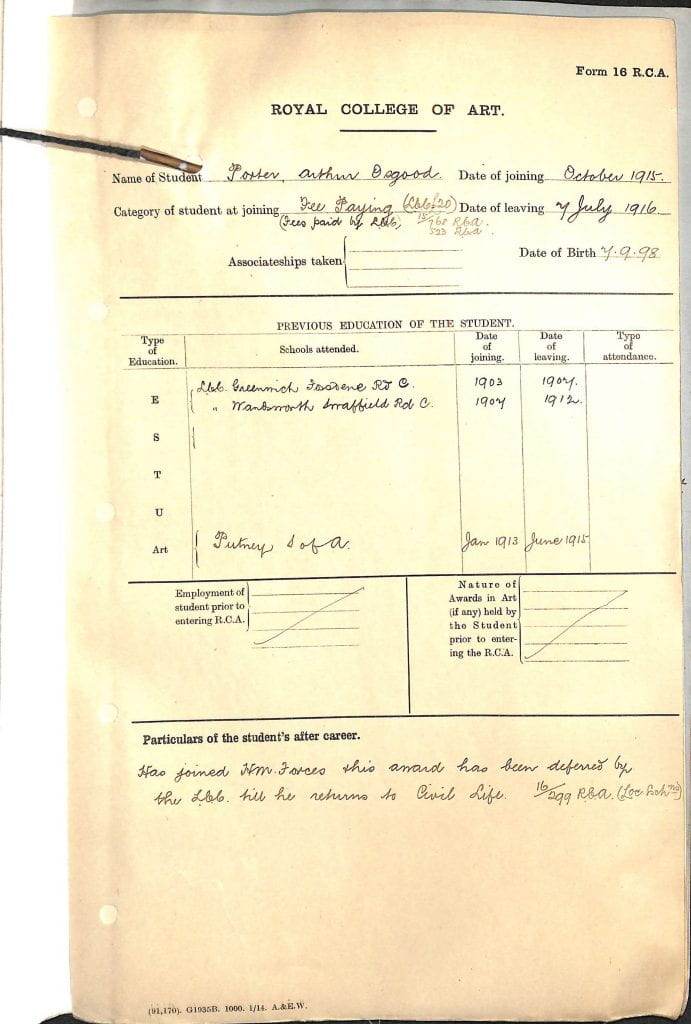

Born: 7 September 1898

Died: 21 March 1918

Studied at the RCA: October 1915–July 1916

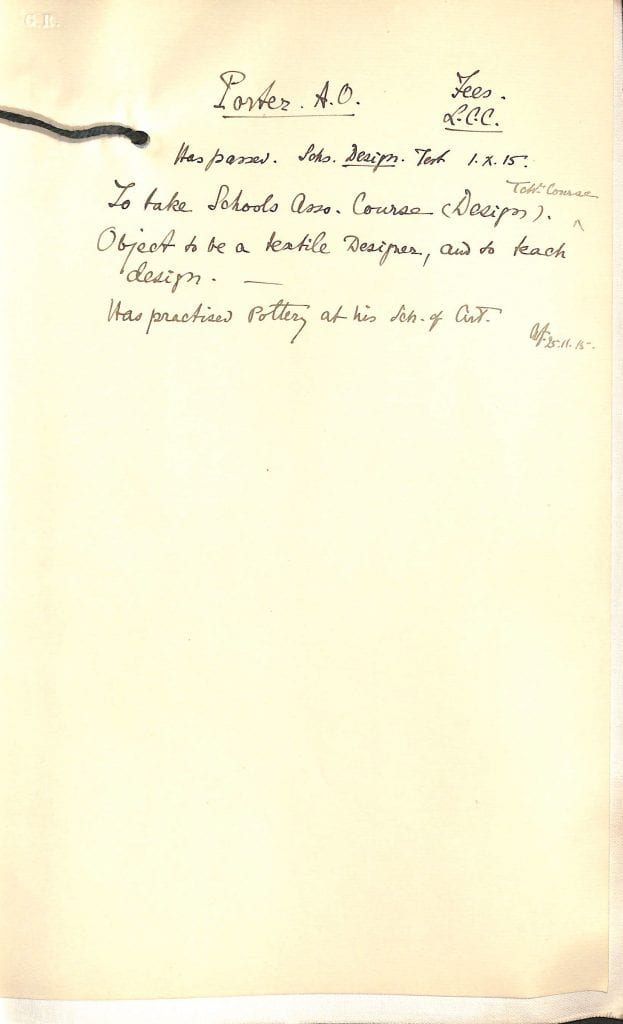

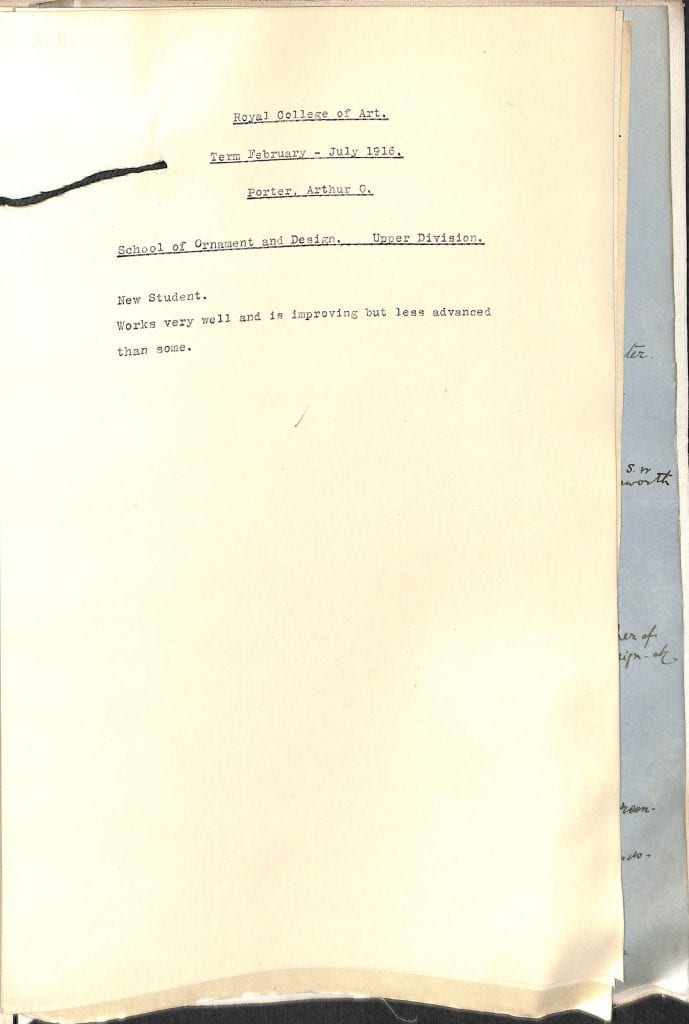

Arthur was the only son of a Welsh-born London police officer, also called Arthur, and his wife, Eliza. At the time of the 1901 census they are also noted as having one older daughter, Ada (another daughter having died in infancy), who was nearly ten years old when her brother was born. By the time war broke out the Porters were living in Wandsworth, his father having apparently retired by his early forties, while Arthur was in the middle of his two years at Putney School of Art. A year later he began at the College with a London County Council (LCC) award. His file suggests he was hoping to become a textile designer and/or teacher of design. When his first, and only, College report was written in February 1916, there are a couple of dismissive comments from Architecture’s Professor Pite, who unwittingly reveals his frustration at Arthur’s (and other students’) lack of interest in his subject, balanced with the observation that Arthur was a ‘good worker – improving steadily’. It was also noted that he was not ‘yet of military age’. In July, however, at the end of his second term, the seventeen-year-old Arthur joined ‘H.M. Forces’, with his award deferred ‘till he returns to Civil Life’.

Too young for overseas service, Arthur began at ‘home’ in the Army Service Corps (ASC). The ASC took responsibility for delivering supplies and equipment, and were divided into hundreds of companies that did not belong to particular regiments or battalions. Up to, and possibly beyond, November 1916, Arthur seems to have been learning to drive motor vehicles, and, while there are no records of his time with the service, he probably continued with them until he reached his nineteenth birthday the following year, and was old enough to be sent abroad. By November 1917, instead of continuing in the ASC Arthur had begun his training as a machine gunner, probably at Belton Park Camp, Grantham, in Lincolnshire.

Frustratingly, Arthur’s soldier file has not survived, so pinpointing exactly when he left for a base camp in France is not easy. What is known is that recruits were desperately needed at the turn of the year, with many established units forced to amalgamate in the face of their high losses, and at a time when rumours of an impending German attack grew day by day. The once proudly Scottish in origin 51st (Highland) Division (now part of the Third Army), had already begun to recruit more broadly. Records suggest that Londoner Arthur, along with 9 other ‘ORs’ (ordinary ranks) joined the 154th Machine Gun Company (MGC) at the end of January 1918. In February they were brought together with three other MGCs to form the new 51st battalion Machine Gun Corps of the 51st Highlanders, with the 154th becoming their C company.

It was trebly unlucky for Arthur that he was inexperienced, that he arrived during a problematic restructuring and, even more significantly, that the poorly defended area between Cambrai and Arras, where his division was based (in Fremicourt), provided a very useful target for the German army. When the eventual attack came a few weeks later, it apparently surprised British commanders, who had thought nearer the coast was more likely. As dawn broke on a foggy 21 March, a massive German bombardment had already begun (totalling over a million shells in five hours) and the 51sts found themselves, as did other divisions of the Third and Fifth Armies, suddenly confronted by overwhelming numbers of German soldiers, lead by elite storm troopers, during the first phase of Die Kaiserschlacht (the Kaiser’s Battle): an attempt to turn the course of the war that very nearly succeeded.

In the actual and metaphorical fog of war only ill-defined glimpses of Arthur can be found in the following hours and days. A post-war account of the 51sts shows Arthur (now an Acting Corporal) and Merseysider Private Gordon Pipe in a watercolour sketch, manning a machine gun point at Velu, on the Beaumetz-Morchies Line near Bapaume, south east of Arras. The account has more to do with the bravery of a commissioned officer than with them, but nonetheless provides a basic narrative that is, unsurprisingly, less clear in the war diaries. Such was the rapidity of the attack, with unit after unit overrun, retreating, outflanked, under-supplied and unable to communicate what was happening, that there was little time to compile even basic statistics until days later, with some dates in the eventual entries evidently muddled. However, it did become clear that the German army had punctured the line in this area, putting Amiens under threat, with many thousands of men from the Third and Fifth Armies killed, injured, and missing by the end of the week. These thousands included Arthur and Gordon.

The following June, when the offensive had run out of energy, both Arthur and Gordon were recommended for Distinguished Conduct Medals (DCMs). The notice of Arthur’s award, published in September, hints at the terrifying reality of the situation they found themselves in that March, and begs numerous questions about how the information was gathered and when:

‘For conspicuous gallantry and devotion to duty. This N.C.O was in charge of the machine guns at a strong point which had been formed when the enemy’s advance had penetrated part of our line. He inflicted losses of the heaviest description on the enemy, whose further progress he checked for some time, holding on to his post to the last and firing the gun himself when all the gun members had become casualties. His coolness and disregard of danger were a fine example to the men who he had collected to man the strong point, and on whom it had a marked influence.’

A handwritten date on the DCM register, the post-war account of the 51sts and two Red Cross POW enquiry cards (one from his brother-in-law and the other a possible girlfriend) note either his presence in the field or missing ‘from’ or ‘since 23.3.18.’. Why then was his date of death later accepted as two days earlier? It might be simply that the last time he was verifiably seen alive (rather than could not be found) was on the first day of the attack, which was also, poignantly, the first day of Spring.

Arthur is commemorated on the Arras Memorial in Pas-de-Calais, France, and on St. Anne’s Church Memorial in Wandsworth.