4.1 Online survey findings

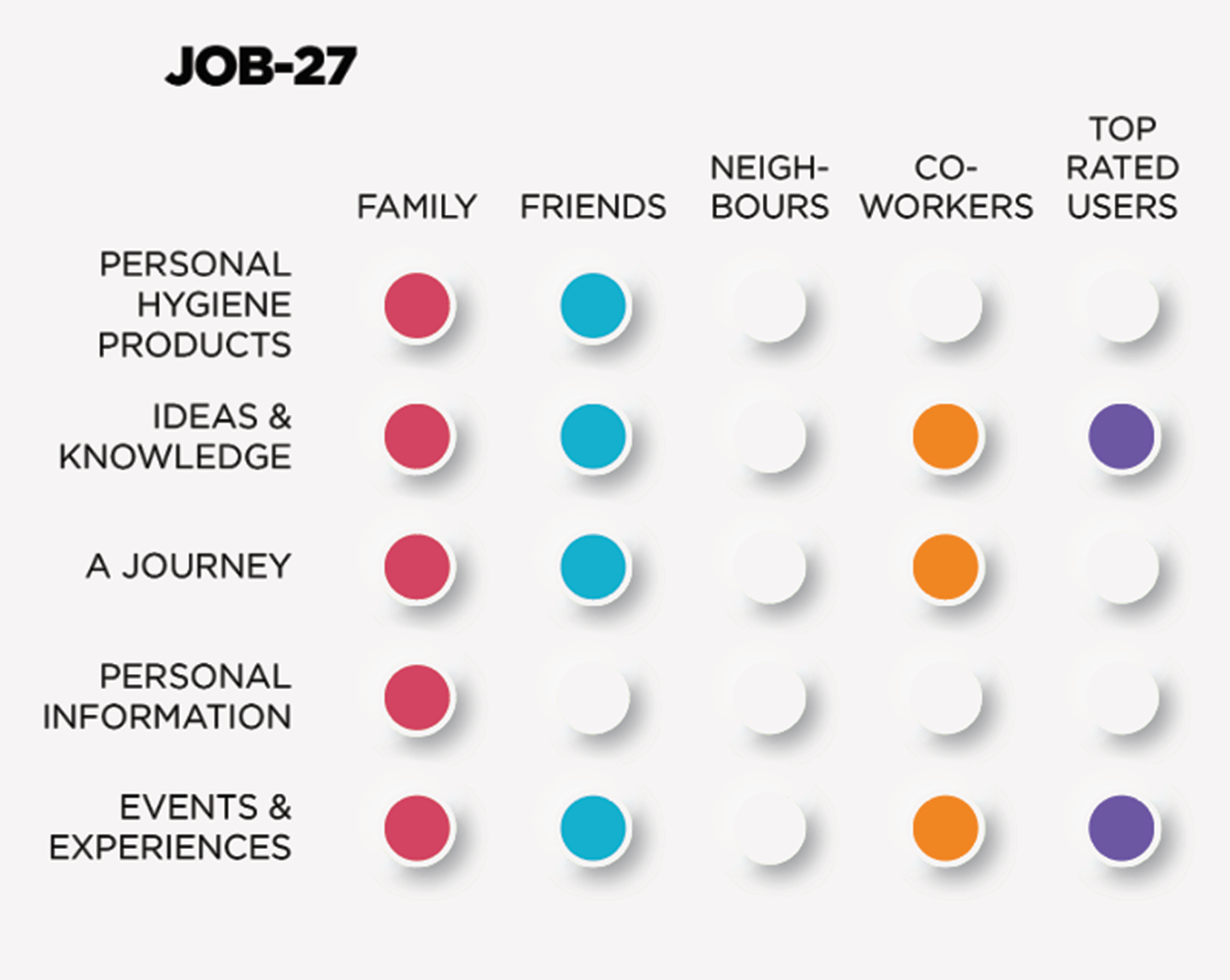

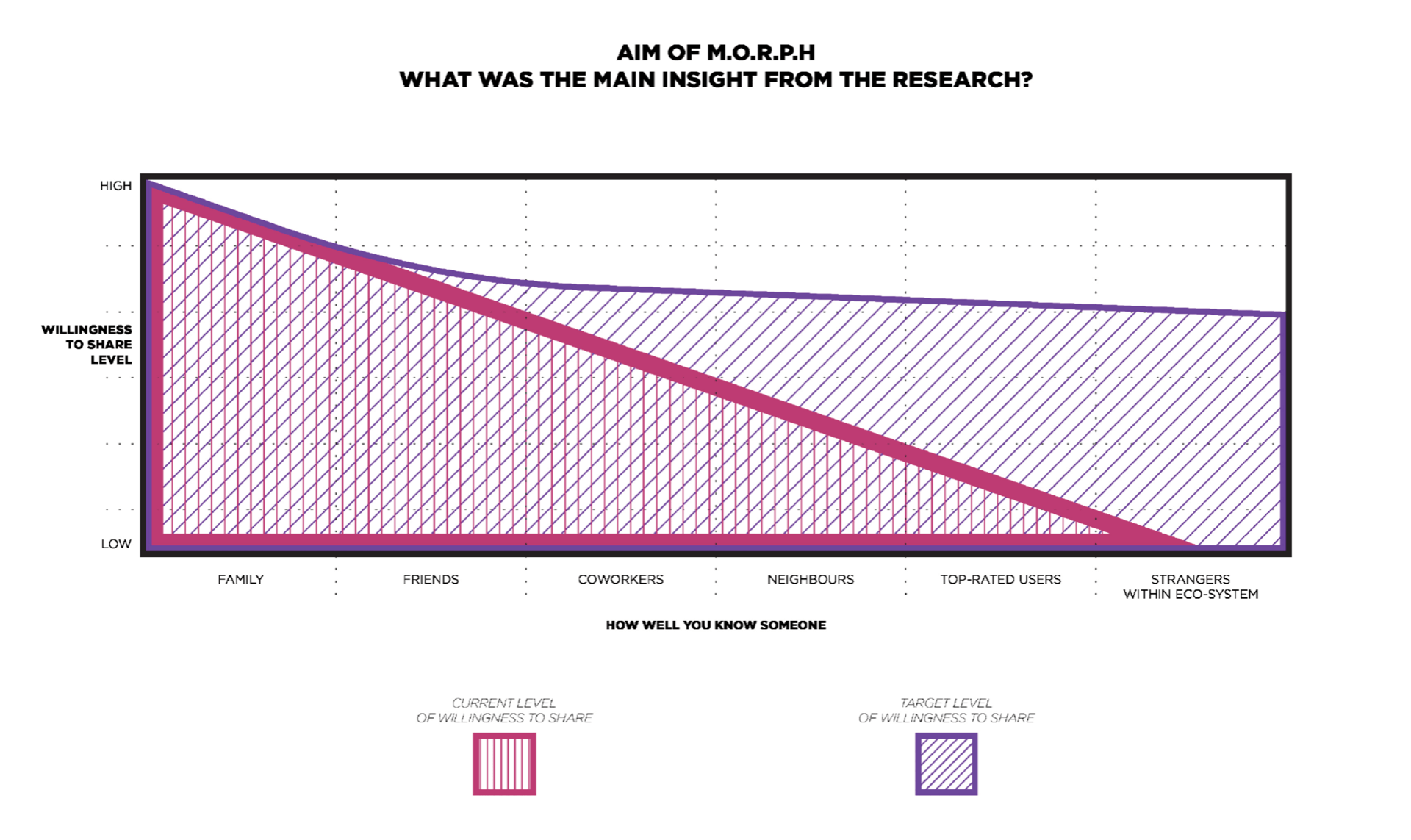

The data collected from our online surveys shows that people are more willing to share possessions, services or vehicles with people they spend time with and know rather than strangers. Individuals indicated that they trust vetted, regulated systems as well as those rated by other users, especially if the systems have internal or external monitoring methods. The main motivations people have for using sharing services are primarily convenience and access followed by value for money and low cost. Barriers to sharing were their concerns regarding cleanliness, personal safety and privacy. Regarding shared mobility, participants’ answers indicated that they perceived the key benefits to vehicle and ride sharing schemes are that they are better for the environment, use resources more efficiently, are cheaper, reduce congestion and are more socially responsible as well as offering value for money. When sharing a vehicle with strangers participants emphasised the need for adequate space between the users, some felt that screens or dividers could separate them and provide privacy, whilst others expressed the desire to have the opportunity to interact with others in the vehicle and socialise. A full summary of online survey results can be found in our report (click ‘DOWNLOAD FULL REPORT’ at the bottom of this webpage).

4.1.1 Use of Shared Products and Services

The survey participants’ main motivations for using a service or product were convenience which received the highest responses in both surveys (70% survey one and 63% survey two). Value for money, access and low costs were also important to their motivations. Being ethically responsible motivated fewer of those taking part in survey one (3%) whilst 9% of survey two chose this, perhaps because most were older in this survey.

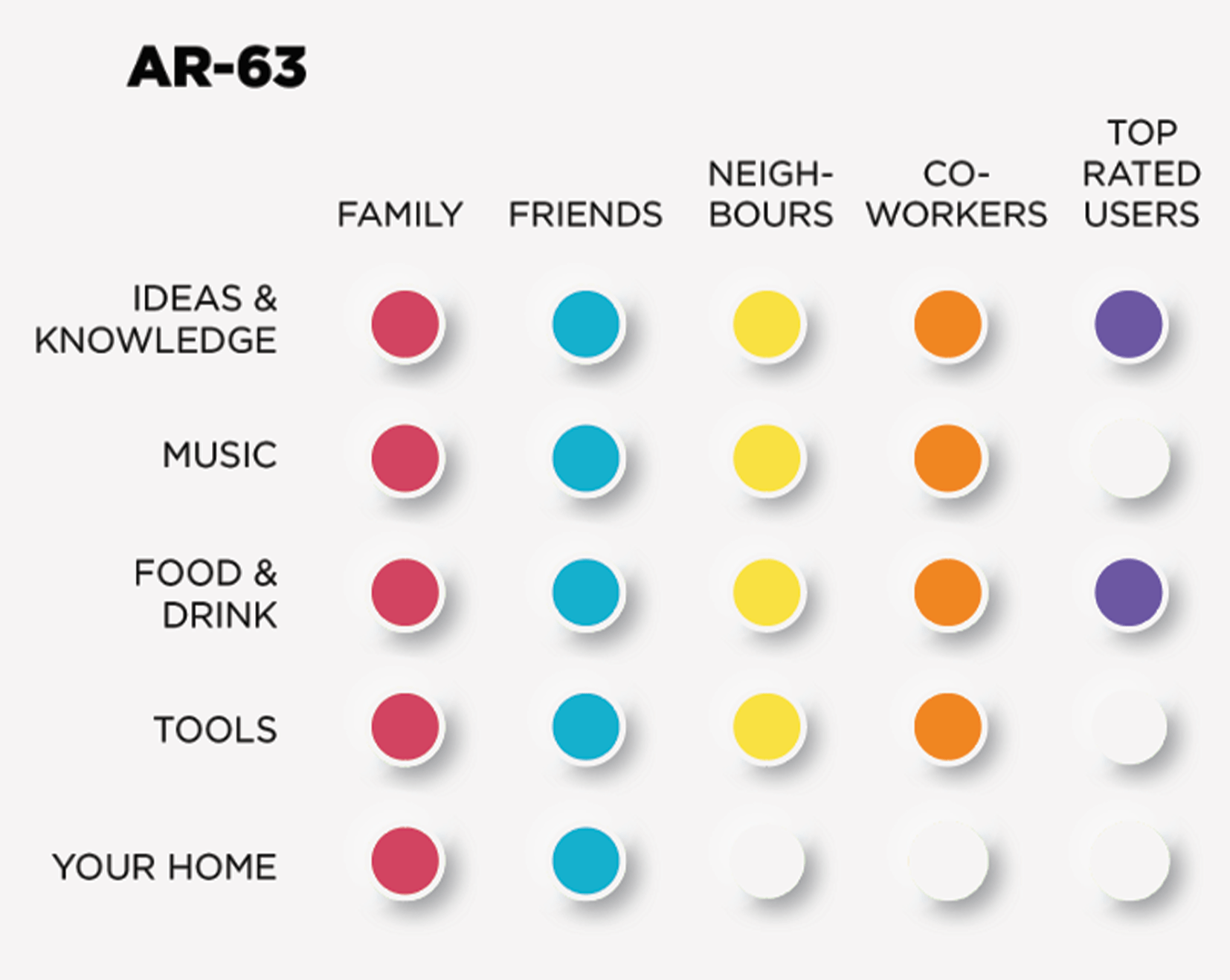

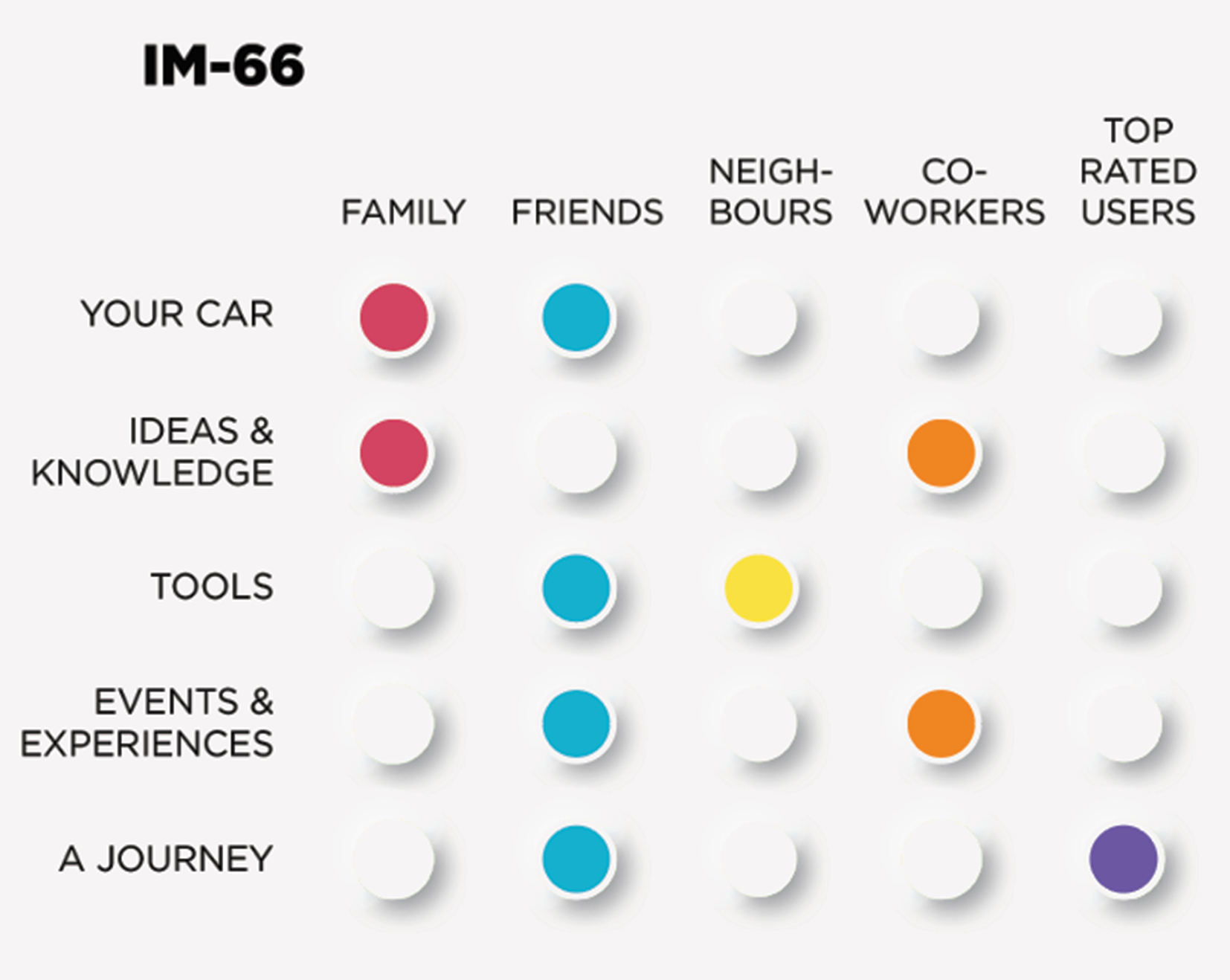

4.1.2 Sharing with Others

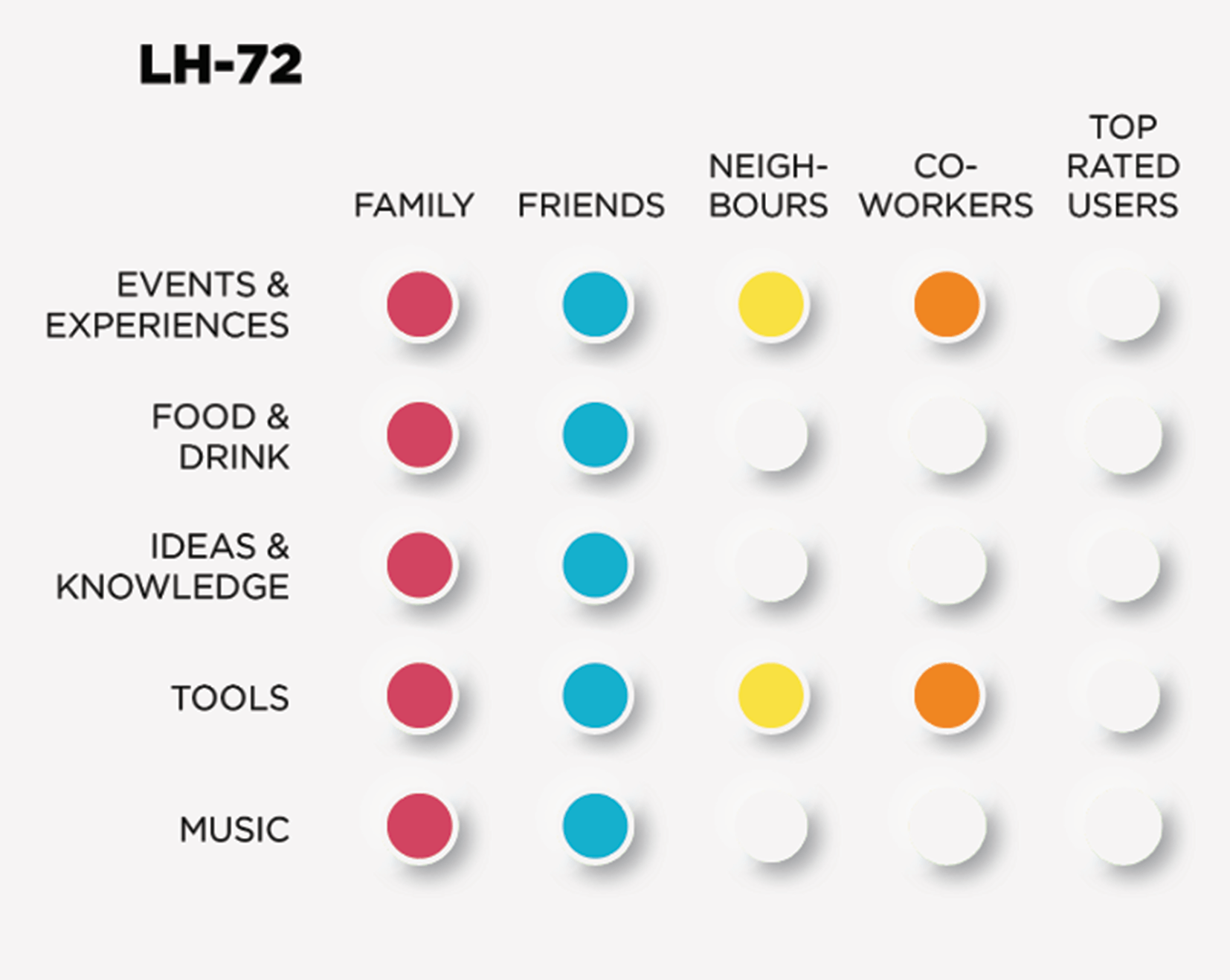

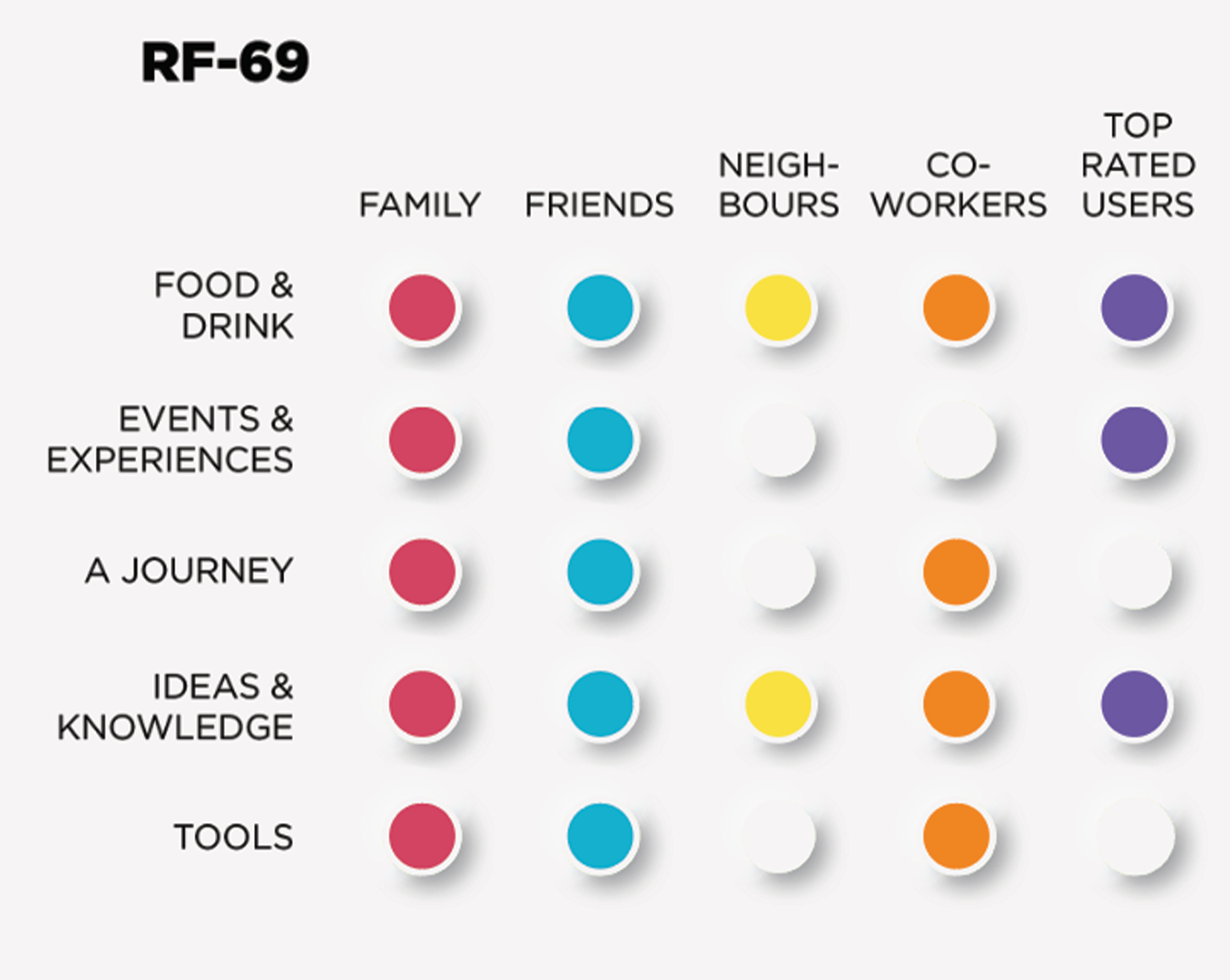

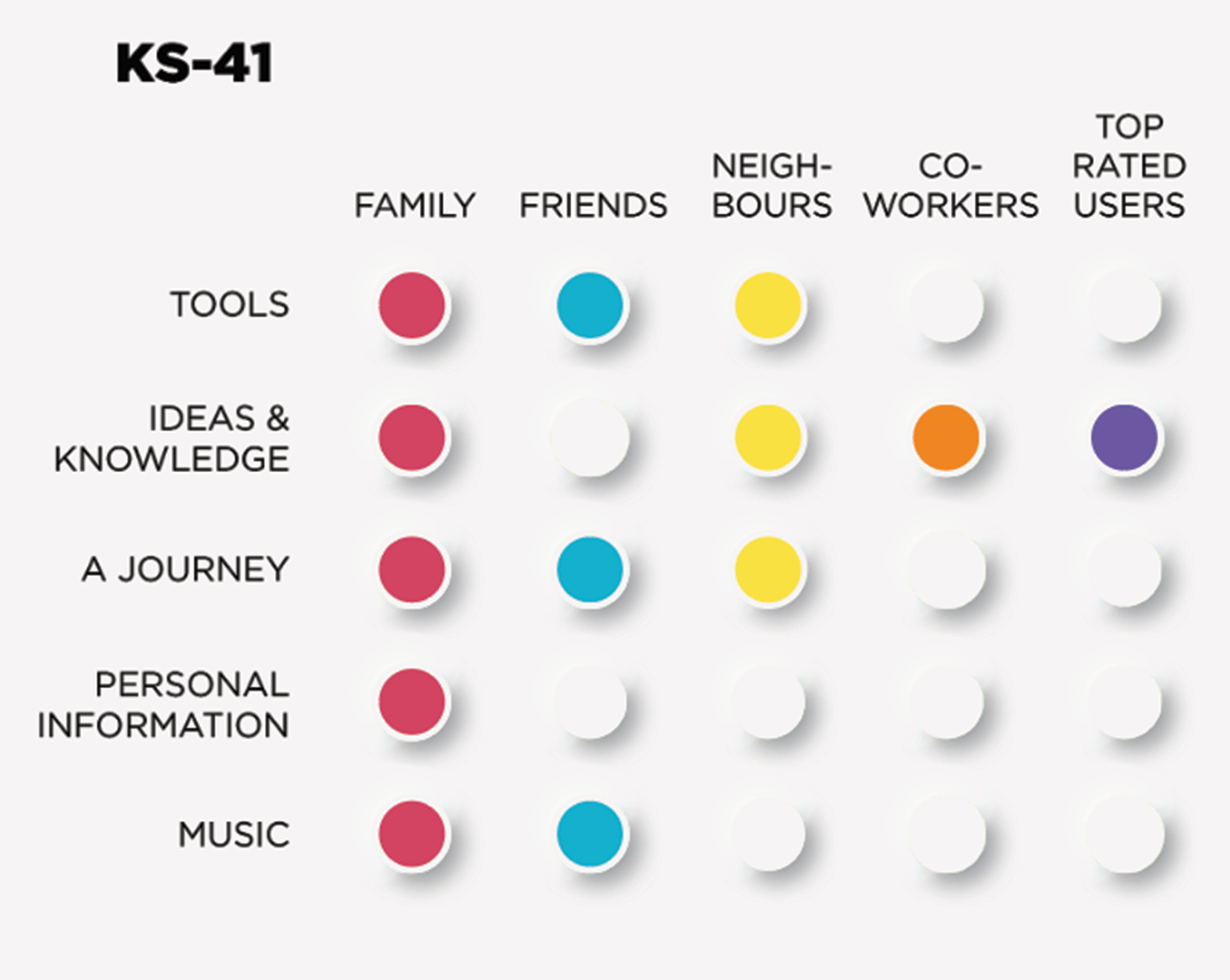

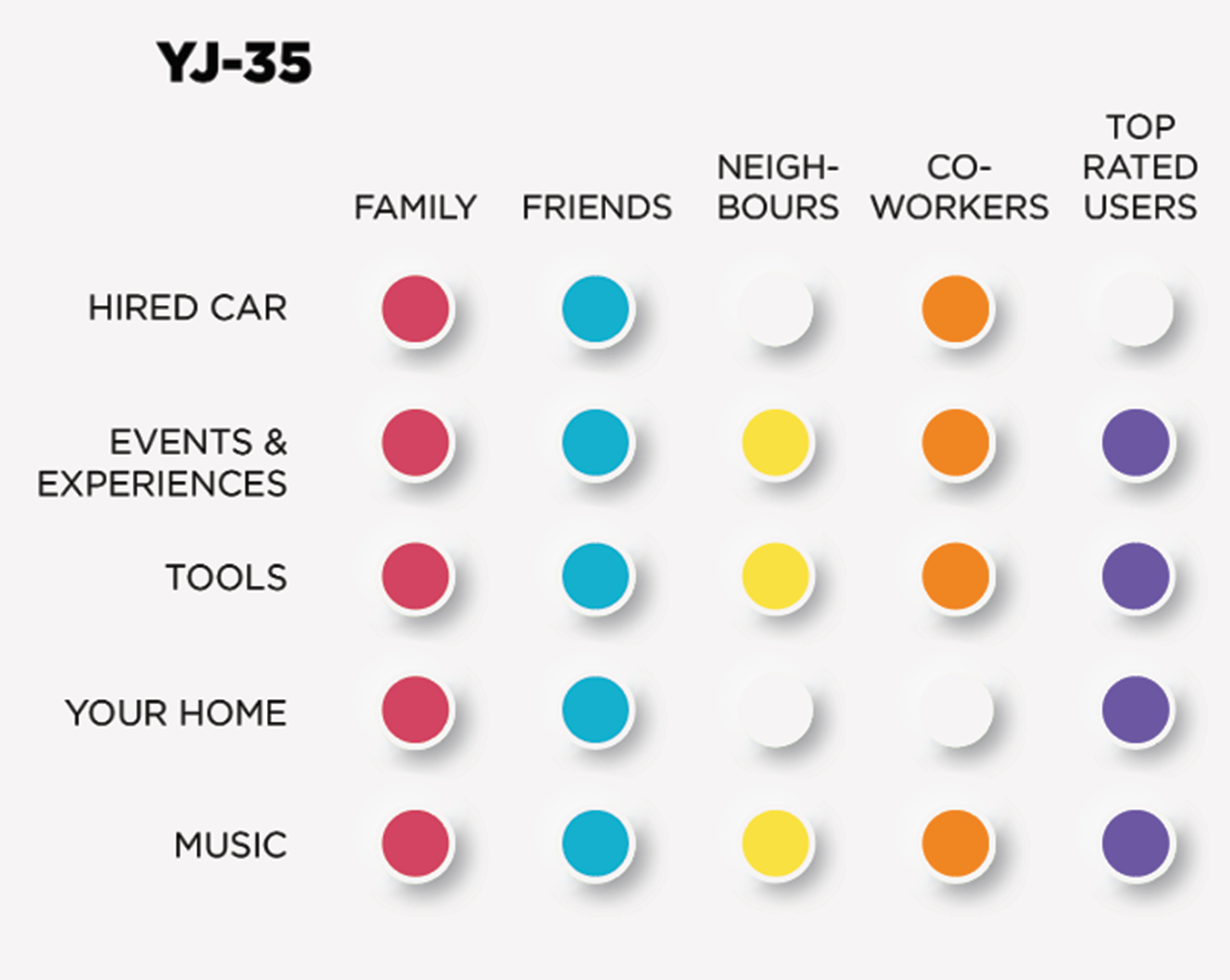

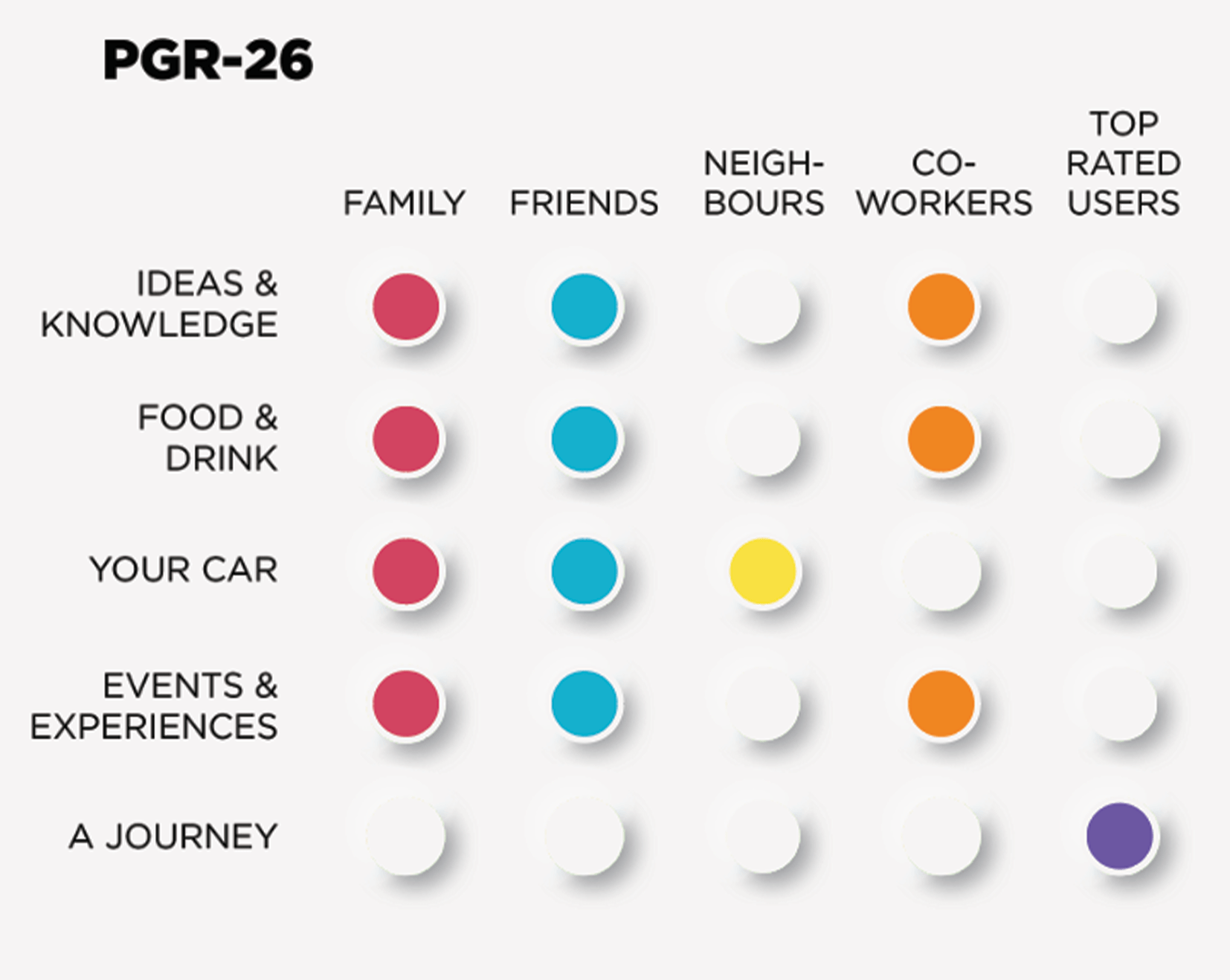

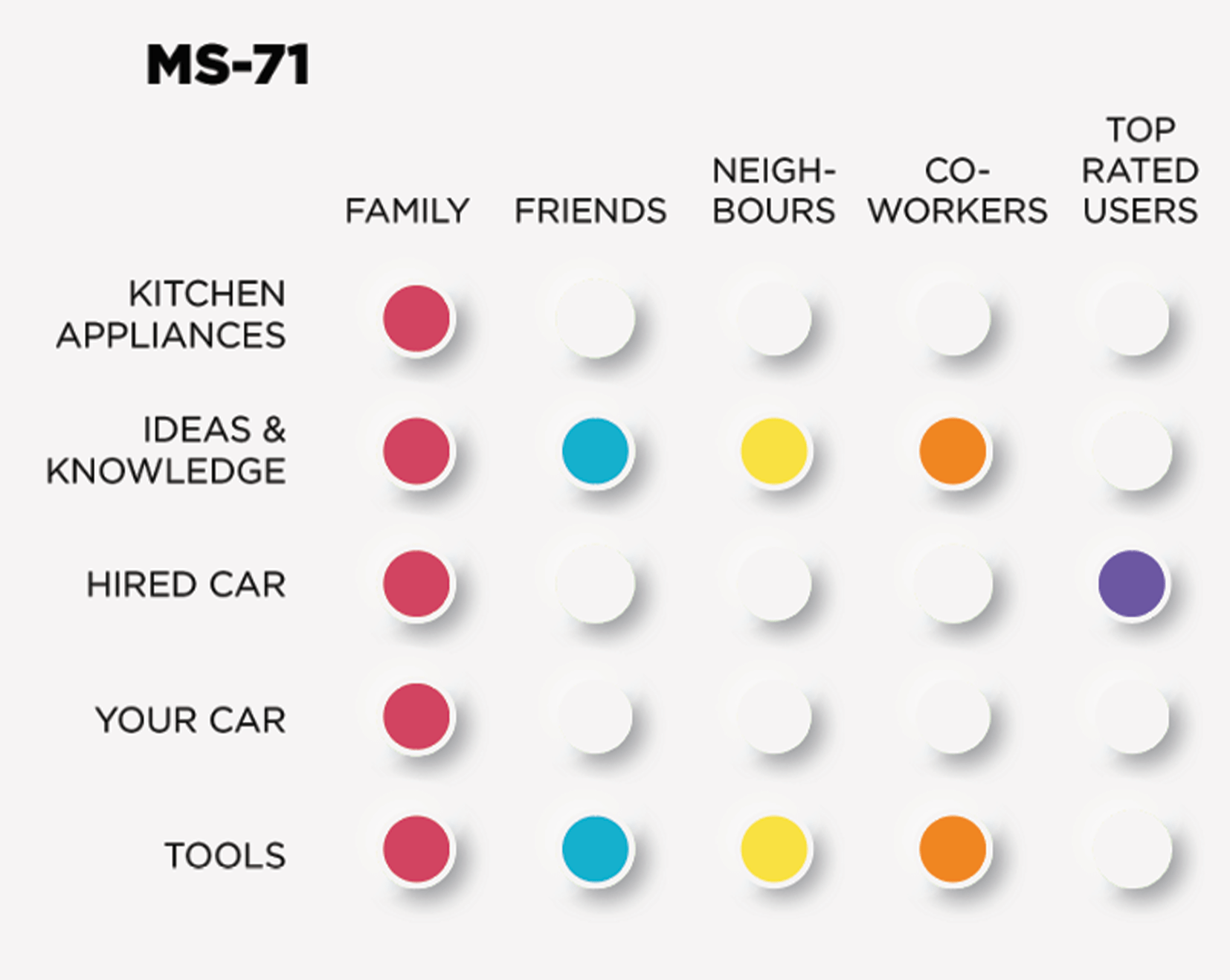

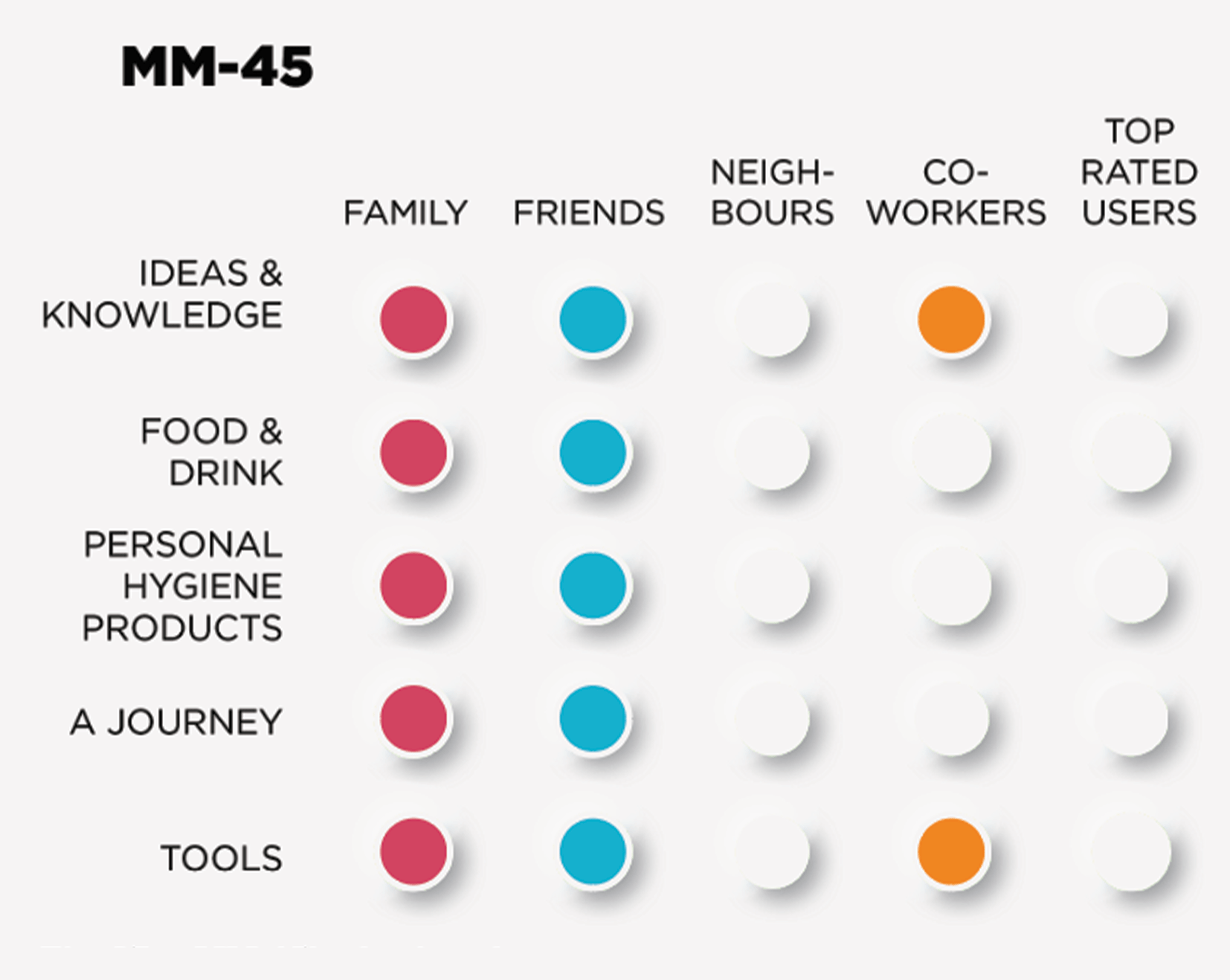

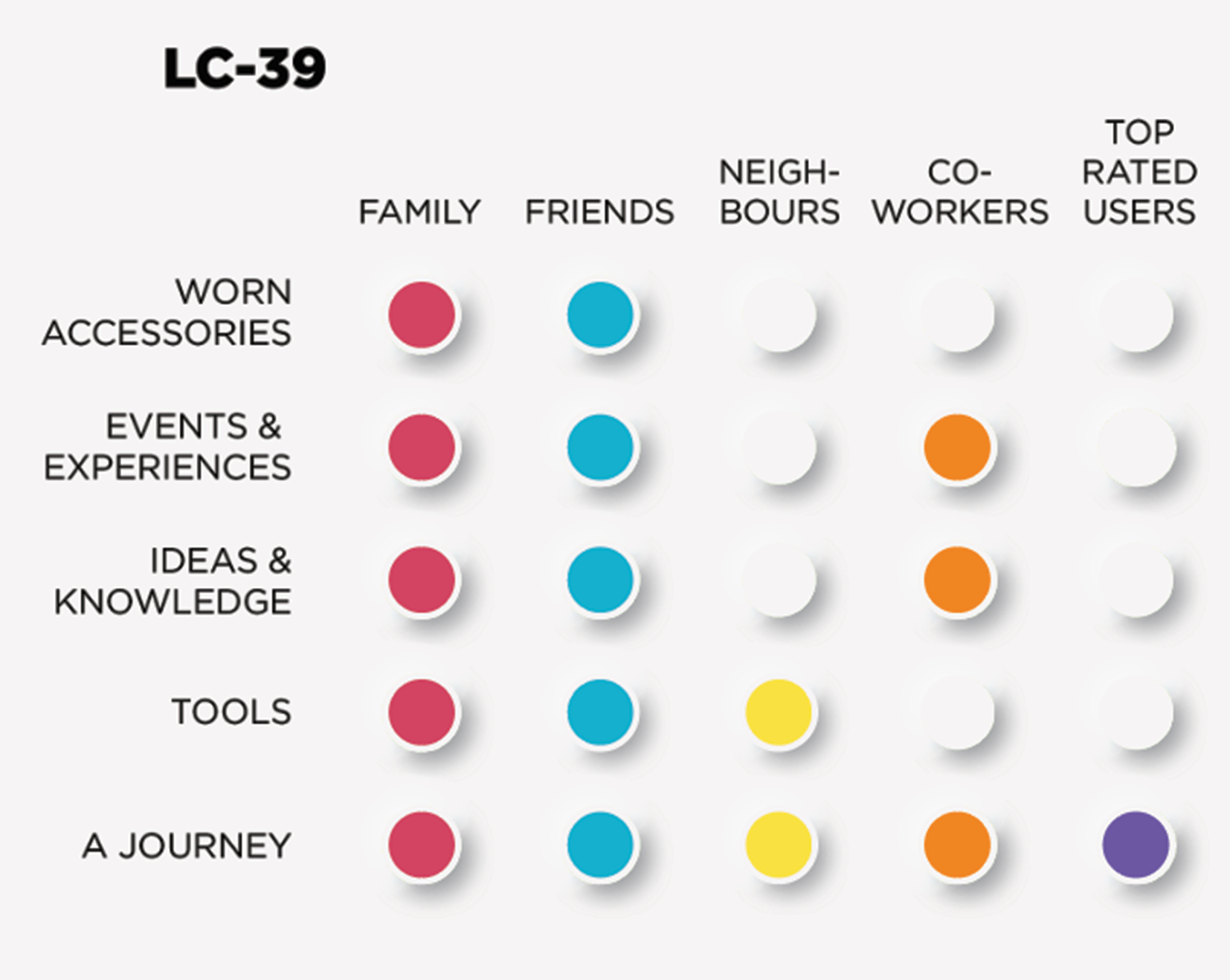

When questioned what they were willing to share with people they knew, a majority from survey one would be very likely to share a journey – taxi service, Uber, etc. (55%), while the survey two participants were most likely to share tools – power tools, ladders, paint brushes etc. (46%). Regarding ‘sharing with people they don’t know’ several participants in survey one were likely to share a journey with strangers (49%), while in survey two were very unlikely to share a journey (46%) with people they don’t know. The top three barriers to sharing in both surveys were cleanliness, safety and privacy.

4.1.3 Benefits and Concerns of Sharing vehicles

The key benefits of vehicle/ride sharing schemes perceived by survey one’s participants were better for the environment (71%), a better use of resources (70%), low cost (65%) and reduced congestion (55%), while in the second survey were the same but in different priorities: low costs (51%), better for the environment (40%) and reducing congestion (37%). The concerns people have about using shared mobility schemes are mostly about personal safety. The concern of not having when they needed a vehicle was the next highest concern in both surveys. A higher number of respondents on survey one (mostly female) said they would have trust if they could use an app to report any concerns to the regulator whilst travelling, or use an app to track their journey in real time or if the journey was monitored by the regulator.

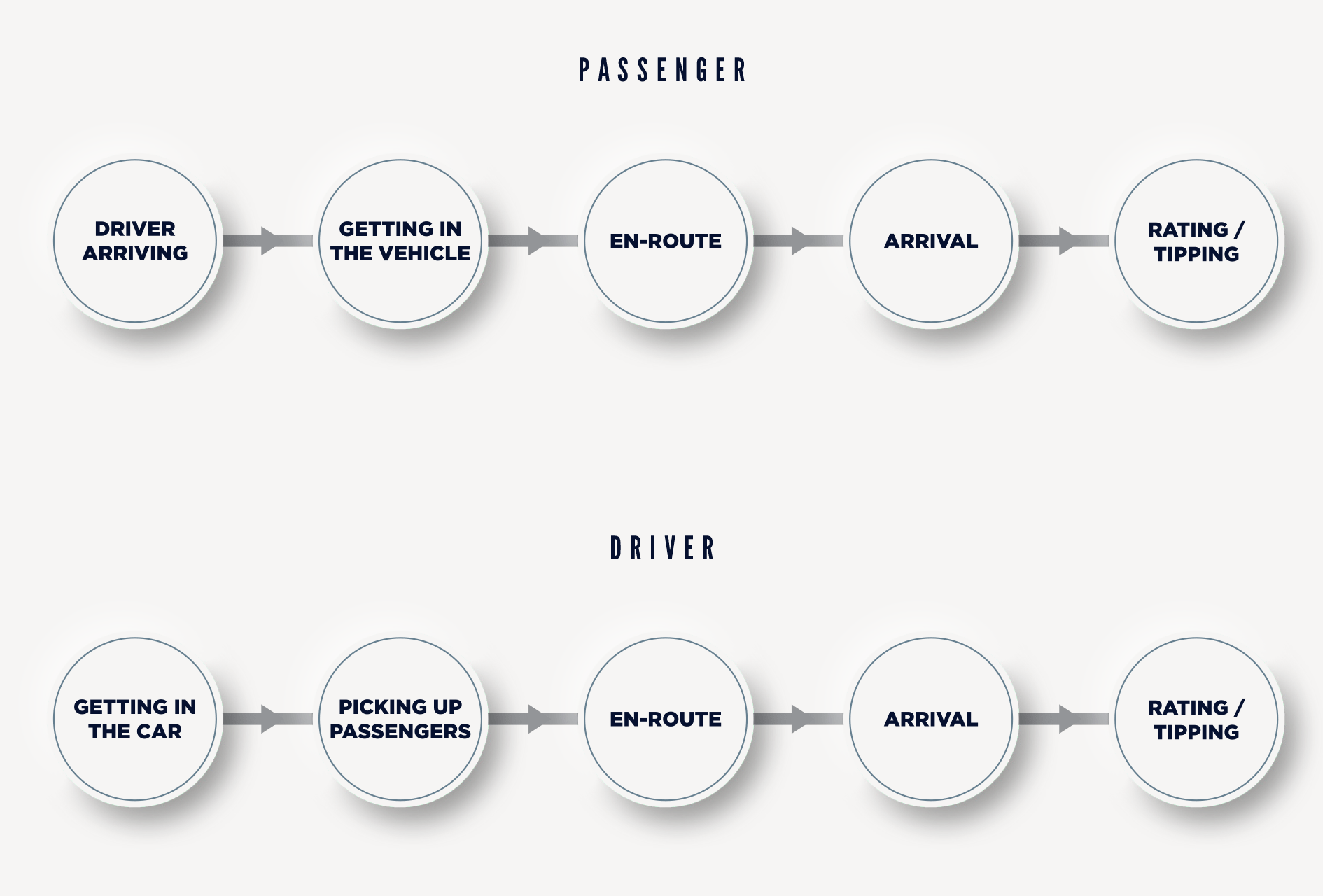

4.2 Findings from the user enactment workshops

The workshops enabled us to gain insight into people’s general sharing experiences as well as their mobility sharing experiences both with people they knew, such as family, friends, colleagues or neighbours and with strangers. Some participants gave their perspective as drivers while others who don’t drive shared their passenger experiences instead. Their general sharing experiences included sharing accommodation, subscriptions and equipment. The most frequently mentioned short journeys they shared a vehicle either as a driver or passenger is commute, some described sharing journeys with family, friends and co-workers for longer trips such as holidays. Positive as well as negative experiences were described and participants spoke about how they felt on their journeys. Good feelings included community spirit, sociable, fun, entertaining and less agreeable feelings arose from disagreements and conflicts, weight of responsibility, feeling tired or not being comfortable. When talking about what they would like to change to make the current Uber like vehicle space more sharing friendly, the workshop participants indicated minor changes such as phone charger and charging pads, children’s booster seats, digital support and services such as selecting the route and being able to open passenger doors if the driver locked it.

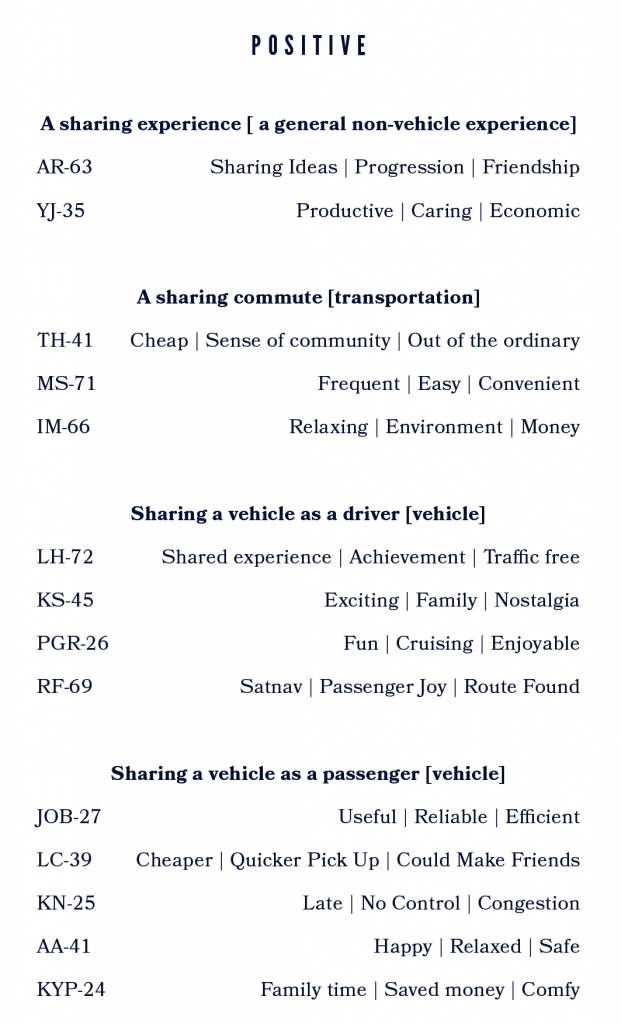

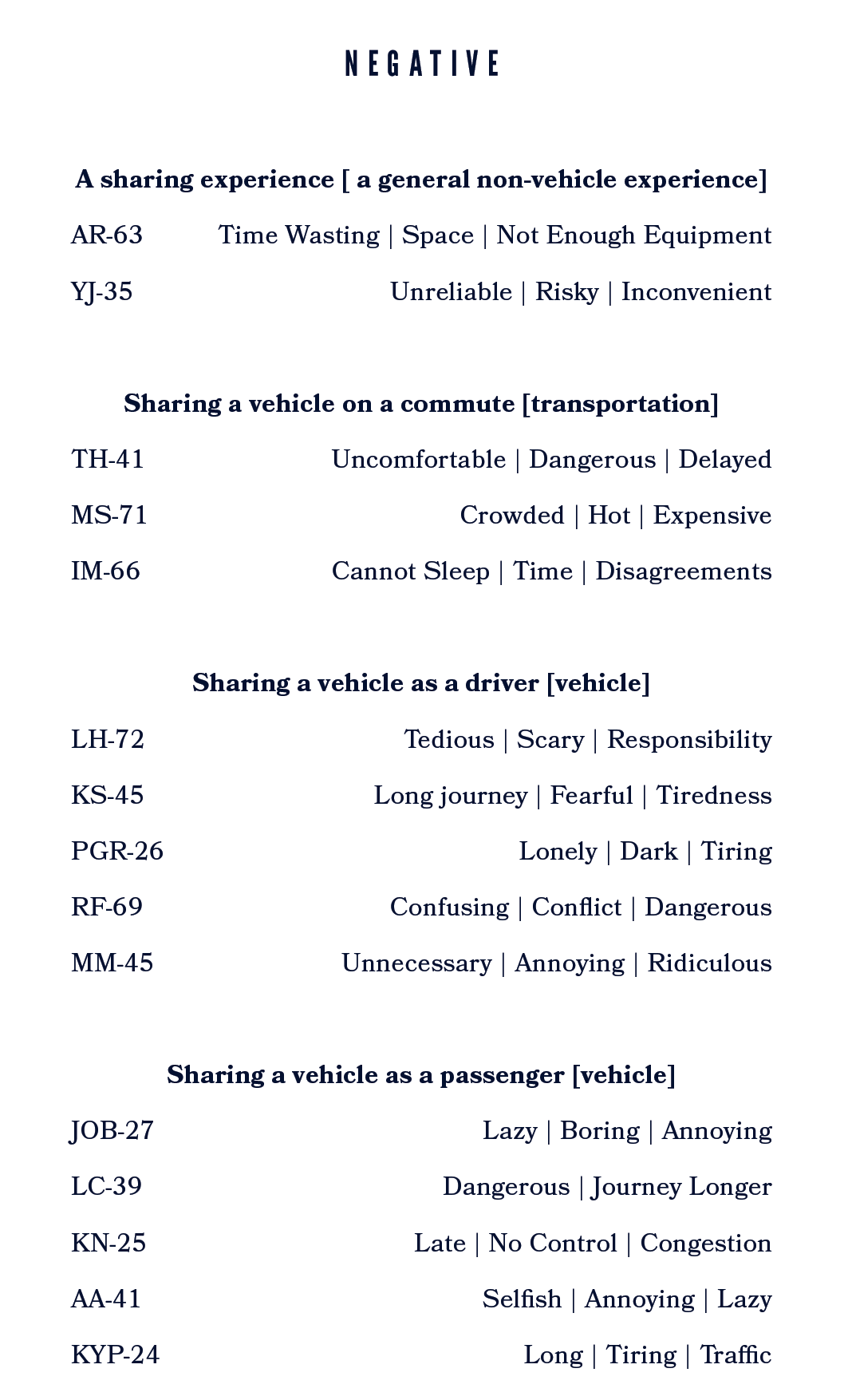

4.2.1 Storytelling and mapping

In asking the participants to share a story of their experiences of sharing, a general account of sharing things and various vehicle sharing memories, we gathered a wide range of examples illustrating diverse events. They also discussed what they liked or didn’t like about their particular sharing event which helped us to identify positive and negative themes connected to their stories. (click ‘DOWNLOAD FULL REPORT’ at the bottom of this webpage to see a full list of examples).

Positive themes that emerged from the storytelling session

The experience of sharing public transport in a foreign country is an unforgettable memory for one workshop participant as it became an out-of-the-ordinary event when the bus became stuck, resulting in the person sharing more interaction with the local people than before while they waited outside the vehicle for assistance. Sharing a commute can have positive economic benefits for those participants who travelled to work with a colleague or neighbours as well as for those using public transport and taxi services. The social side of sharing a vehicle as a driver and as a passenger was enjoyed by several participants as they described spending time talking with friends, family and students, listening to nostalgic music, sharing food as well as the journey, and that they felt part of a community.

See Figure 16 that shows three keywords each participant chose to describe their positive thoughts on sharing.